25th November 2017

Big dreams and hard work led the Sexton family business from a horse and water-powered sawmill to a modern, integrated harvesting and sawmilling operation.

— Paul Iarocci

Susan and Kevin Sexton.

In August 2017, BTB visited the harvesting and sawmilling operations of Sexton Lumber based in Bloomfield, Newfoundland. Owners, Kevin and Susan Sexton have built a thriving, vertically integrated business. It begins in the rugged, scrappy spruce and fir forests of the North Atlantic island and ends with Sexton Trucking delivering dimensional lumber to customers within the province. The company also has a market reach throughout the Maritimes and into the United States.

Along the way, round wood is processed at the twin line small log stud mill at a rate of 60 million board feet per year. Round pulp as well as chips and recovered residue are trucked to Corner Brook Pulp & Paper. The mill and harvesting operations employee around 100 people. The company rates as a major success story in the province, overcoming many challenges along the way through hard work, forward thinking and common sense. Kevin Sexton tells the story in his own words.

My dad started his first sawmill in the early forties when they were using horses to pull the logs and the water propelled wheel that would drive the saw. The watermill we’d call it. I never came along until the sixties and during summer holidays and after school, that’s where I’d be, at the mill — stacking lumber or playing in the sawdust. So I grew up in the sawmill business. As time went on, I moved away from it and got into trucking. But as my dad got older, I realized that I was going to have to make a decision. Was I going to be in trucking or was I going to continue in the business?

Susan and I bought a chipper and debarker in 1992 and started producing chips for the Abitibi pulp mill in Grand Falls. We had it set up in the yard at my Dad’s sawmill. We produced two loads a day. Susan and I and one other fellow would debark and chip all day. Then after the shift was over, I’d take off to Grand Falls with the chips. I’d make the two trips and be back home again for the start of the shift in the morning. That wasn’t easy. I was running on two and three hours of sleep for weeks and weeks like that.

We eventually bought another truck and hired a driver. He started hauling the chips and I stuck around and helped at the mill a little bit. After four years, my dad was ready to retire. That’s when we took over the mill.

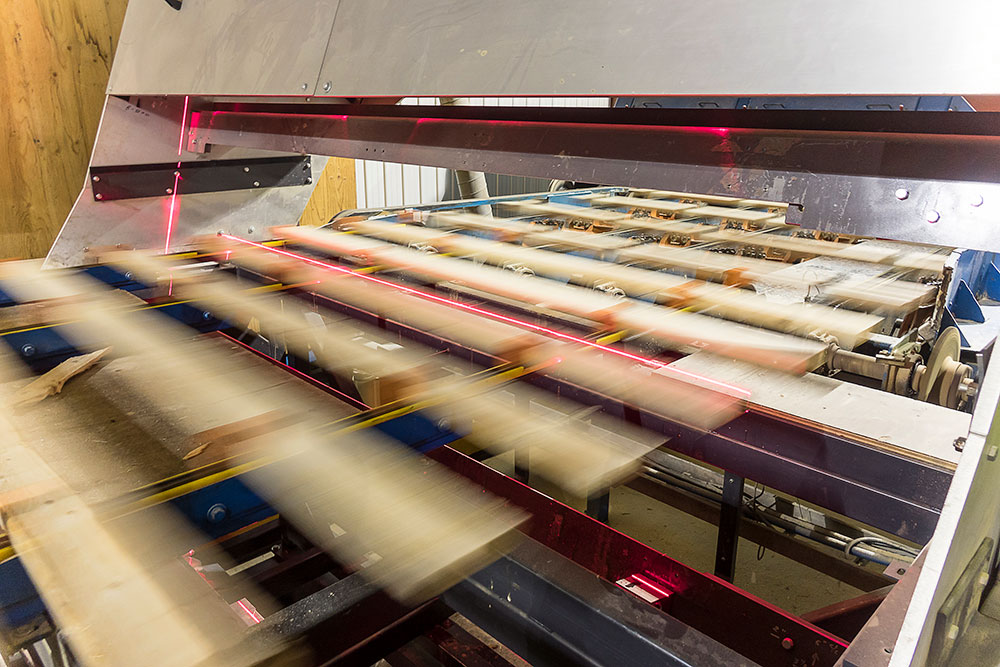

One of the two saw lines at the mill. It all happens very fast. At this stage the machine is rotating the log according to the scan in preparation for sawing.

It was only just a small mill but we envisioned being the biggest sawmill in the province. That was our goal and we took a different approach than some other mills in the province. We researched newer technology. That’s one of the things I believe in, technology. We saw the trend of logs getting smaller, so I bought the first chip and saw mill that came into the province in 1996. It was a used machine and I had to get it trucked out of Montana. It came here in five or six trailer loads. There were pieces everywhere. We set it up and it looked like a spaceship to us. I mean we had never seen anything like it. We had our trials and tribulations but we stuck with it and ran that old machine for about four years.

I have no idea how we did it, but in 1999 we financed a new sawing machine — a HewSaw from Finland. And that was a big step. It was almost two million bucks and it was the latest and greatest in sawing technology back then. I’ve still got the machine. It was a big investment for somebody with 50 bucks in their pocket and not knowing anything about it. I had dreamed about this HewSaw for years. The salesman in BC, he was tired of talking to me. We went through, I’d say, four or five different finance companies to get the machine financed. I honestly think that those lending agencies that financed it believed in us. And that’s why we got the money, as far as I’m concerned. They believed in us.

The Abitibi mill closed in February, 2009. By that point Kevin had struck a deal to send chips to Kruger in Corner Brook. When Abitibi closed, the provincial government took back the timber rights and reallocated the volume to the sawmills that were previously buying saw logs from Abitibi.

Tigercat 1075B forwarder. According to Kevin, “In the woods, steel means something.”

We were buying our logs from local contractors and the Abitibi Bowater pulp mill in Grand Falls-Windsor. We had no harvesting equipment whatsoever. When the mill closed, that was the beginning of our harvesting days. When we started, we didn’t think Tigercat was in our reach, as they were expensive machines. It became something like with the sawing machine. We dreamed of having Tigercat machines after seeing them at DEMO 2008, but when would we get there? So we just kept on harvesting.

Tigercat is almost like a family and I firmly believe that once you start buying Tigercat equipment you are a part of that family.

– Kevin Sexton

It was the Atlantic equipment show in 2014 where we first met Chris Baldwin. He showed us around and we looked at that 1075. That show would have been in April and Wajax delivered it to us in July. We put it in the woods and looked at it side-by-side with our other forwarders. We could have melted down the other two and there wouldn’t be as much steel as there was in that 1075. In the woods, steel means something.

Over the years I’ve had the opportunity to purchase quite a few different brands of equipment. I’ve met the people associated with each company and I’ve seen the service that comes with it. There is no doubt Tigercat equipment is by far superior to other brands and they have proven it. But technical service is also crucial. Tigercat is almost like a family and I firmly believe that once you start buying Tigercat equipment you are a part of that family.

Last year Sexton Lumber harvested 150 000 cubic metres with three feller bunchers, including a Tigercat 845C and 845D. The bunchers are followed by in-stand processing: three H845D harvesters plus four older excavator-based processors. Forwarding is accomplished with two 1075B forwarders and a third aging forwarder that has not yet been replaced. The crew works a single shift, 50 hours per week. Stem size and stand density is what one would expect for a North Atlantic maritime climate with rugged, rocky geology and less than outstanding soil quality. Average size is about ten trees to the cubic metre and stand density averages 1,500 stems per hectare.

Our harvesting costs have gone down. And that’s mainly because of production. Production comes from machines running. Simple as that.

On the track machines, the only failure that I know of was a main pump. We were only down a day and a half. The other buncher and the processors, I don’t know if we’ve had any downtime. On average, the processors are doing ten to twelve cubic metres per hour. We’re not in the big wood. We get two eight-foot [2,4 m] logs and a piece of pulp. Their fuel consumption is much better than the other processors by far. They are probably two litres per hour more efficient than the excavator bases with much more horsepower [260 hp vs 159 hp]. And forget about the fuel. The uptime alone makes them more efficient than anything else out there.

The harvesting crew is producing eight and nine foot logs and currently supplying 60% of the sawmill intake of 1 000 cubic metres per day. That translates to annual mill production of 60 million board feet of lumber.

Scanning the lumber for quality.

Our pulpwood from a typical block averages 25 to 30 percent maximum because we’re accepting logs down to a three-and-a-half inch diameter top at the sawmill. That is just a single two by three. We mill two-by-three, two-by-four, two-by-six and two-by eight stud wood. The maximum that we can process is thirteen inch diameter. So we’ve got what they call a butt reducer. And a lot of the time, it is just the flared butt that we have to grind down. The fibre goes to our dryer and is sent to the pulp mill for hog fuel. So that fibre is recovered.

There are so many steps in the process — from the time the harvester goes in the woods to when that piece of lumber is wrapped and ready for the customer. There are so many things that are out of our control that could cost money.

Our primary market for lumber is here in Newfoundland. We sell some in the Maritimes and the remainder, probably 40%, goes to the US. My plan is to install a third sawing machine. We need to bring our annual harvest up to 250 000 cubic metres and increase the mill output to 100 million board feet.

Another recently completed project was the installation of a finger-joint plant. The rationale? To address the high incidence of trim backs – six and seven foot lumber that is only marketable in the US, and commanding a poor price at that.

The value of the shorter lumber trim backs we were producing was really low, plus we were not recovering anything in the saw mill shorter than six feet. So there was lumber going to the chipper that had four feet of good wood. Now, we want to recover all that and send it to the finger-joint plant — not to make eight foot lumber because we’re producing plenty of that. But there is a good market here for long-length lumber for horizontal use. And most of what’s being consumed is coming from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Quebec. So instead of sending short lumber south and getting basically nothing for it, let’s turn it into a product that we can sell right here at home and increase the value big-time.

We also put in a small pressure-treating plant. Not to compete with the big guys — we just want to add a little value to some of our products and offer it to local customers that we sell lumber to every day.

Our harvesting costs have gone down. And that’s mainly because of production. Production comes from machines running. Simple as that. That’s what Neil Greening, the “finance minister” always tells us: it’s not about the capital cost, that is just one component. Everything has an impact. You know what really hurts us is machines that don’t produce. Downtime is a killer because you never gain it back. It’s gone forever and the cost of producing wood from that machine, obviously, it’s going to be higher on average because it has to offset all the lost production.

Sexton runs three H845D harvesters.

Kevin names his wife Susan and Neil Greening, the controller, as the two team members that are absolutely critical to the operations and success of the business. Susan manages Sexton Trucking which is focused on delivering finished lumber to the customer base within the province. She also manages all the contract haulers for roundwood and chips.

Susan looks after all the drivers and she takes all the calls when they are broke down in the middle of the night. But Susan also knows this business as well as I do. She knows every move that a machine makes at the mill. So Susan’s role is whatever she needs to do. If there’s an issue in the woods and I’m not available, she’ll look after that. If the mill is broke down for some reason, she can look after that too. We share the responsibilities.

Kevin and Susan’s latest buncher, an 845D.

And Neil — the finance minister as I call him — has been with us for nineteen years. He’s an accountant but he sure knows this business and we rely on him heavily. He knows the recovery for the sawmill and the fuel consumption for the harvesters. Every week, he’s doing reports and following recovery. Neil is the one that will tell me if a machine is starting to burn more fuel in the woods. At the end of the week, we know what the wood cost is per cubic metre for that week. We’re right up to date.

That’s one of the things I believe in, technology.

– Kevin Sexton

You’ve got to know what your cost is. And it’s too late six months down the road. We need to know weekly. Our recovery in the mill is tracked hourly. We’re averaging 285 to 287 board feet of lumber per cubic metre out of the sawmill. If we drop down for an hour to 280, we don’t hit the panic button. But if our recovery consistently stays down by four or five board feet per cubic metre, that’s a pile of cash at the end of the day. We are doing 1 000 cubic metres in a shift. If we lose five board feet per cubic metre, that’s 5,000 feet of lumber that we don’t have. It could be something as simple as dirt on a scanner and it’s not reading the diameter of the log correctly. And if we go on for six hours like that and all we needed was a tissue to clean a laser, shame on us. Knowing our numbers is crucial.

Kevin relates what it felt like to make another enormous investment and enter into a venture that he had no practical experience with. Suddenly in 2009, he and Susan were loggers.

It was scary because I didn’t know the logging end of it. I just tried to get a couple good people around me that did know logging. And I figured we could apply what we knew about the sawmill side of it to the harvesting side. Like tracking and controlling cost, recovery and inventory. So that’s what we did. It’s not like there are two business models.

We apply the same principles daily in the woods as we do here at the mill. Now, I’ll be first to admit it’s been much more difficult to actually do that because we are here. And the woods operation — when you’re not onsite every day — it makes it more difficult.